In many ways, my own birding journey began with my book Fire Birds: Valuing Natural Wildfires and Burned Forests. That’s when my birding mentor, UM Professor Dick Hutto, showed me the critical importance of burned forests and the spectacular birds that colonize them. It’s also when Braden and I began birding avidly. Since then, we have explored burned forests many times and they have become some of our favorite places to bird. Last week, we were excited to check out one of our area’s newest burns, last year’s Miller Creek fire area, about an hour from our house. To reach it, we headed all the way out Miller Creek and then wound our way up dirt roads until we reached the burn at Holloman Saddle. On the drive, we passed through terrific riparian and conifer habitat, and Braden could pick out Yellow and Orange-crowned Warblers, Swainson’s Thrushes, and Willow Flycatchers through the car window. At about 6,300 feet elevation, we reached the burn, parked, and began exploring.

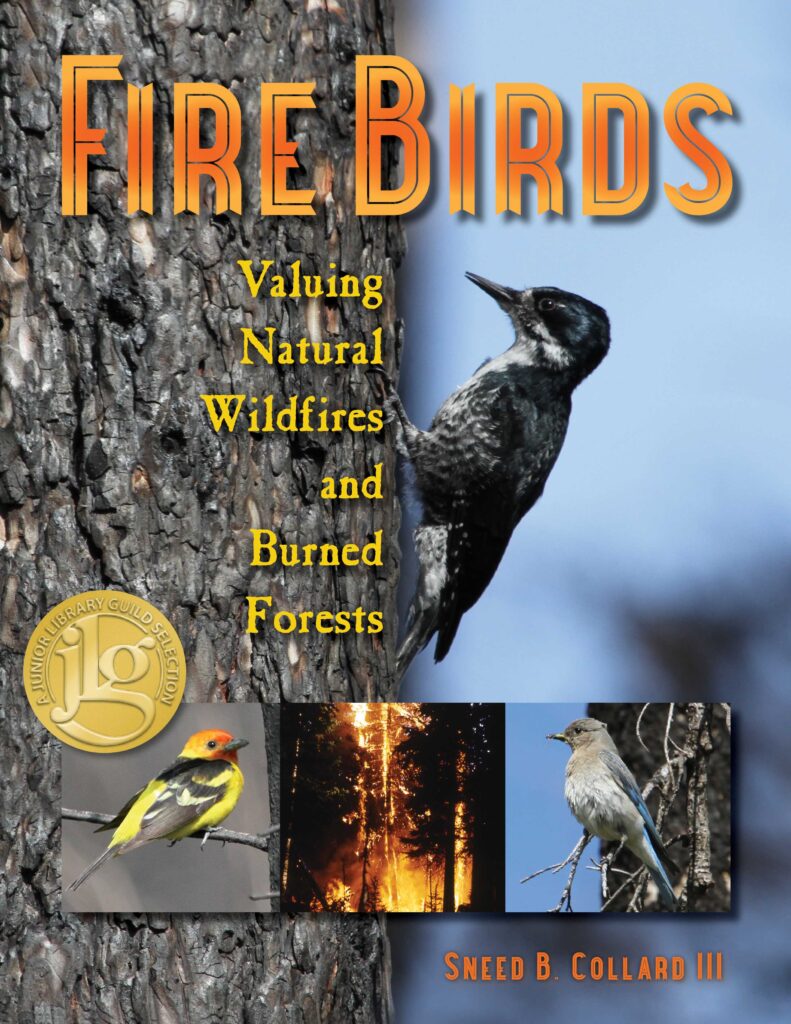

Researching and writing Fire Birds: Valuing Natural Wildfires and Burned Forests set me firmly on my birding journey—and propelled Braden and me to start birding burned forests. The multiple award-winning book is a great primer for kids and adults on many little-known aspects of forest ecology. To order a copy, click anywhere on this block!

Thanks to Dick’s tutoring, I had some experience sizing up burns and at first, this one didn’t seem ideal. Three birds essential to “opening up” a burned forest are Black-backed, American Three-toed, and Hairy Woodpeckers. These birds hunt wood-boring beetle grubs in the newly-charred forest and along the way, drill out cavities essential for other cavity-nesting birds. But Dick’s research had shown that Black-backed Woodpeckers need larger-diameter trees to nest in, and the forest that greeted us now mainly seemed full of smaller-diameter trees. I also saw stumps where larger trees had already been removed—another huge problem in human (mis)management of burns.

Through decades of well-intentioned Smokey Bear messaging, we have all been taught that all fires are bad, bad, bad. Even when a natural fire does occur, the forestry Powers That Be have taught us that humans must somehow “save” a burn by salvage logging it. For those unfamiliar with it, salvage logging involves going into a burn and removing trees that retain commercial value. The problem? These trees are exactly the larger-diameter trees that woodpeckers need to drill out their homes and, in the process, provide homes for dozens of other animal species. Salvage logging also often severely compacts forest soils and removes the seed sources (cones of burned trees) needed for the forest to regrow. This means that we now have to pay people to replant the burn site—when the forest was already perfectly equipped to replant itself.

Nonetheless, shortly after Braden and I began walking, we heard the distinctive drumming of either an American Three-toed or Black-backed Woodpecker. These can be distinguished from other woodpeckers because the drumming noticeably slows at the end. To find out which bird was drumming now, we began making our way down a steep hillside toward some larger trees, but the burned ground proved very crunchy and we may have spooked our quarry before we got eyes on it. Disappointed, we climbed back up to the road, and continued walking. Fortunately, the forest around us sang and flitted with bird life.

Almost immediately, we began seeing Mountain Bluebirds, one of Montana’s most spectacular species. MOBLs are well-known “fire birds” and their vivid blue plumage looks especially striking against the blackened trunks of a burned forest. Today, we saw these birds everywhere. During our three-mile walk, Braden recorded seven of them, but we both agreed we probably undercounted.

Suddenly, a large shape took off from beside the road and spread its wings as it glided down into the woods. “Dusky Grouse!” Braden exclaimed. It was one of the birds he most wanted to see since arriving back in Montana the previous week. Hoping for a better look, we crept down after the bird and, sure enough, espied it sitting quietly in the shadows. We enjoyed it through our binoculars for five minutes and then slipped away, leaving it in peace.

Except for the mystery woodpecker that had drummed earlier, we had not heard a trace of other woodpeckers, but what we did hear was astonishing: wood-boring beetle larvae actually munching away inside of the dead tree trunks! I’d been told that one could hear these, but with my crummy hearing, I didn’t believe that I ever would. Sure enough, in several places, we listened to these big juicy grubs take noisy bites out of the wood!

Finally, we also heard tapping on a large tree ahead. Braden got his eyes on it first. “It’s an American Three-toed,” he exulted. We could tell it was a female by the lack of a yellow crown, and we settled in to watch this amazing bird. It was working its way down the trunk, flaking away burned bark, presumably to check for insects hiding underneath. Once in a while, it stopped and really began pounding away after a beetle deeper inside the wood. It sounded like someone driving nails into cement!

As we continued our walk, we also saw Hairy Woodpeckers and another three-toed, this one a male. Woodpeckers, though, were just some of the birds making use of the burn. We got great looks at Townsend’s Solitaires, Red Crossbills, American Robins, Dark-eyed Juncos, Yellow-rumped Warblers, and Chipping Sparrows, and heard both Red- and White-breasted Nuthatches. Most of these are classic “burn birds” and we felt exhilarated to see them.

At a couple of places, unburned green scrubby areas abutted the fire boundary, and it was fun to see birds dash from these green protected areas into the burn for quick meals or nesting materials before dashing back to safety. Many birds, in fact, love to “set up shop” at the boundaries of such two contrasting habitats.

We never did find a Black-backed Woodpecker, but that did little to detract from yet another great birding outing. We vowed to return to this spot the next few years, hoping that no one would move in to “save” this precious forest that didn’t need saving. On the drive down, we also stopped at some of the lower riparian areas for great “listens” at MacGillivray’s, Orange-crowned, and Yellow Warblers along with our favorite empid species, Willow Flycatchers. Amid the current chaos of the world, our burn bird outing offered a fun, revitalizing—and yes, inspiring—break. If you’re lucky enough to have a burned forest near you, we hope you’ll check it out.